It has been one year since my last V8 update. And another busy year it was.

I completed the documentation on the V8.

Both folders have proven their value over and over since, especially during testing.

Before I installed the new fuellines, I immersed them in a cistern to test their airtightness with an air compressor.

Talking about ignition: I milled a container for the EDIS 8 controller.

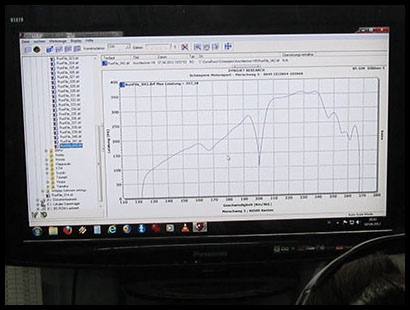

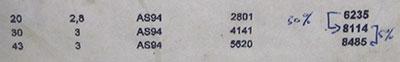

On April 7 2012 we did the second Dyno test. Niels again changed the injector wiring as the bike now has 8 instead of 16 injectors.

Less complex wiring, and easier to control with the motormanagement. And some weight loss for even better acceleration. ;)

Peter didn't want to fall behind and held up some wiring too. Well done, Peter! ;)

The bike started right away, a great moment after such drastic modifications (see previous update).

Me and Klaus (l) enjoy sniffing V8 exhaust gases. It's unhealthy but hey, most nice things are.

Tuning experts Peter and Niels discussed the steps to take.

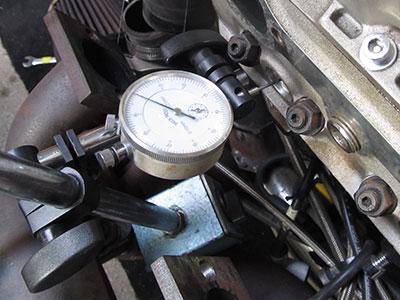

During testing Klaus kept an eye and a tool on still one of the biggest challenges: heat control.

Still far too rich but a nice result to end the day with: 357 rear wheel horsepower @ 1,08 bar turbo pressure.

Click the picture to enlarge it.

During Dyno II we measured, beside the horsepower, the intake air temperature, which was quite high. Hot air has a low percentage of oxygen which is negative for the engine's effeciency and performance.

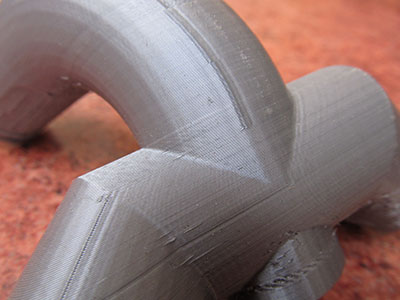

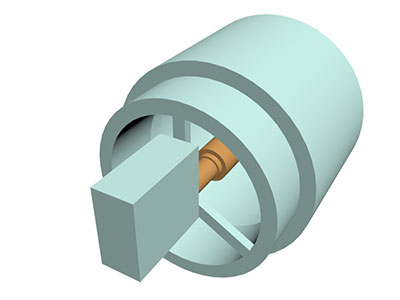

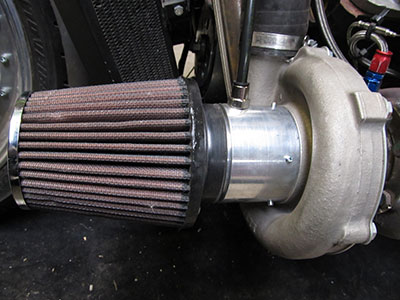

So again a temperature issue. This one might be solved by an intercooler but I don't have any space for such a big part in my design. An interesting alternative is water-alcohol injection; I gathered quite some information about it on the internet, like this picture.

This system is called a 'pre-turbo injection'.

The system works as follows: a sensor in the intake manifold tells the motormanagement system how high the turbo pressure is. The manifold also puts pressure on a water container. If boost pressure is above 0,5 bar MegaSquirt opens both solenoids and a fine mist is sprayed through the turbos into the manifold, cooling the air and raising performance.

Started with four kilos of aluminum ...

... and after some milling, lathing and silver soldering it fitted like a charm.

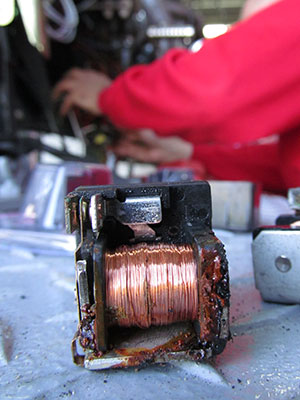

The rest of the day we fought with the lambda controllers. Sensors and controllers are this bikes nervous system; any problem with any of them paralyzes the bike and takes the day.

June 16 2012: Dyno IV. Again lambda complications took a lot of time – one of them even burned out – as did other defect wiring. Bad luck, but that's R&D.

Tuning always start with a rich mixture: it won't get you the best results but it'll increase the chance that the engine will survive this torture.

Although Peter has some huge fans in his high tech testing facility, for a short while the V8 produced more rich gases than the blowers could abduct.

Autotuning from idle to ... yes.

Okay, some sound too, to get a picture:

August 26 2012: Peter, Niels and me had a meeting. No testing this time, just talking about the next V8 steps to take. Reason: Europe regulations are changing fast and I don't want to end this bike without official licence plate and papers. So priority from now on shifts from perfect tuning with brutal results to rideable tuning and getting it streetlegal.

Sounds easy and fast but still there's a lot to be done. For one: the battery died. In the design it had an ideal position (in front of the oil pan) but was killed by my worst technical enemy a.k.a. heat. Finding a cool new place was quite a challenge because there are no really cool places at my bike. And the design had to be protected, of course.

While surfing I came across 3Tek Engineering, a young Dutch innovative company. Sander Prins from 3Tek and I put in a lot of effort to find the right solution for my bike: two new relatively small but very strong Lithium Ion ('LiFePO4') batteries.

I modeled the battery in my 3D program, and a waterproof steel case.

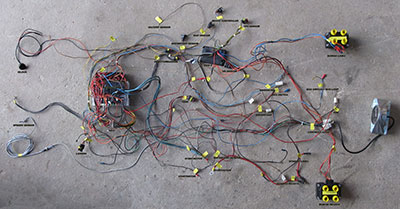

Willy Naves welded both casings.

I love nice welds.

One of the finished products.

Peter and I tested the set to see if they could start the V8: seven times in two minutes was no problem.

From a designer point of view there is simply no perfect place for the new batteries. But there is an acceptable place.

Again there was Trouble in Lambda Paradise: faulty firmware this time.

We replaced the defective boost valve ('PWM') by a new Pierburg N75. As you've read above elektronics is a complex matter, not only for us but apparently even for manufacturer Pierburg, as we read in their manual. A challenge: find out the error in one of the three pink rectangles.

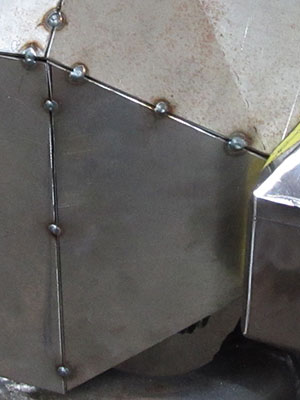

So I decided to enlarge the cooler surface as much as possible. An 8 centimeter extension should enhance the cooling capacity by 25%, and that is substantial.

Chris made the new cooler and suggested a new, slightly bigger fan. He measured the air displacement of the 'old' one (900 cubic meter per hour) and compared it with the new one (1289 cubic meter per hour). That is 43% more.

That should do. And if it doesn't: it still should.

Last months that Peter, Klaus and I visited seventyfive year old bike legend Fritz Egli in Switzerland. We discussed Egli's attempt in 2014 to break his own sidecar landspeed record at Bonneville. And discussed the possibility to take my V8 along with it for the same reason. Nice dream, that's for sure, but priority is getting the bike street legal.

To be continued ... here.